There aren’t many people who can share the same tale about the Chaleur Bay ghost ship that archivist and genealogist Florence Godin can.

It’s mid-August, and the septuagenarian is taking a moment away from her work at the Bathurst Heritage Museum.

Godin has been a working member of the Irish and Scottish associations in the city, collecting their lineages and writing about them, since 1997.

She’s also published 33 books on the history of Bathurst and its surrounding territories. Her voice reflects this passion as she holds onto to every word, savouring it before vocalizing.

There are many histories that she shares with students, seniors, anyone with enough craving for it, but the story that elicits the most response is the ghost ship.

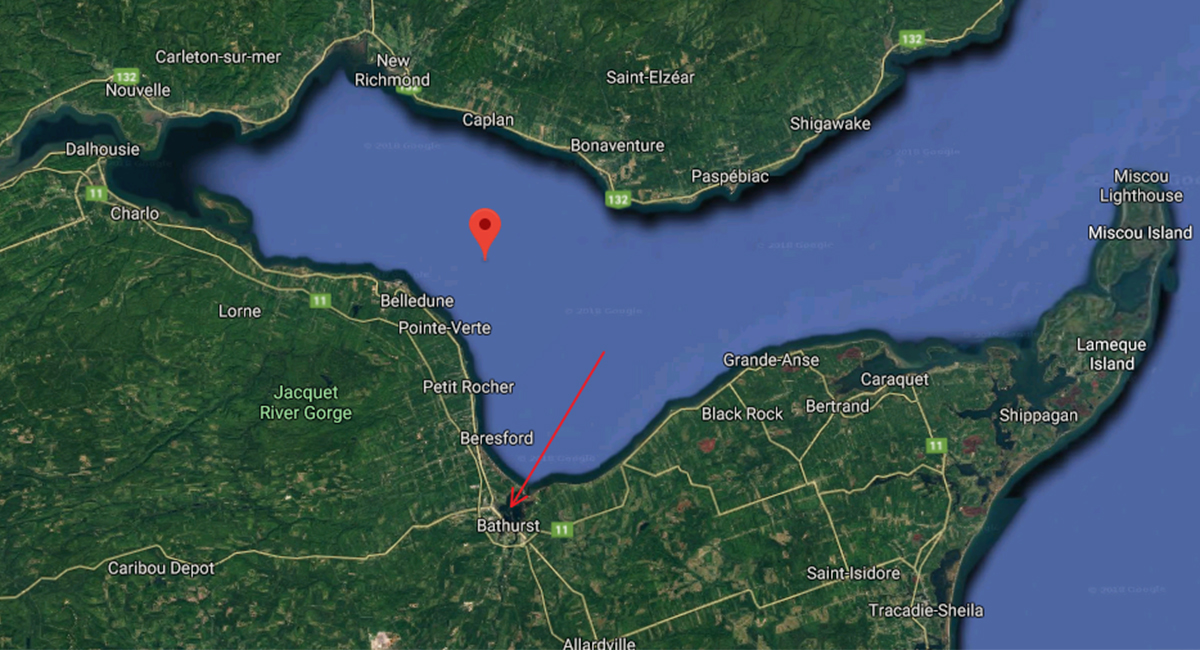

It’s a ubiquitous entity in that haunts the harbour, marina and outer bay. Even a craft beer has taken up the moniker Chaleur Bay Phantom Ship.

“People would mention the phantom ship, and I would tell them, yeah, I saw it out in the harbour,” she says, with a hint of incredulity. “They were just so interested in hearing it and I couldn’t understand why.”

In an instant, she transports herself back to that summer night in the late 1950s. She’s walking north across the Veterans Bridge, the one that connects one side of St. Peter Avenue to another, on route to babysitting for a local doctor.

It was around 9:30 pm, and she looked east across the water, close to the Whites Channel.

And there it was, the Chaleur Bay ghost ship, afire.

“At that age, I never heard of the phantom ship,” she admits.

Behind her, a taxi cab slowed, and the contents, a couple spilled out onto the bridge. Godin told them to turn around and get the fire department.

“There was a wharf. Fishermen would use that wharf and go out in the morning, she recalls. “I thought what happened was the fire burned the rope tied off to the wharf and it floated away.”

But not this evening. The ship had an appearance that was unlike most fishing vessels of the time, and the taxi driver called attention to that, in French.

“That was the only time I looked at it. It was sails. There were big sails,” Godin steers the conversation to the boat’s appearance. ”The people in the car all got out. They were French. They were saying, ‘Look at the people running’.”

The front of the ship in question was facing them. Its masthead a fully carved woman, and on board were clearly people panicking, as well as two large dogs that Godin thought were mastiffs.

There was a woman aboard who was being pulled back by another man. Then another man approached and brandished a sword. The clothing, from what Godin could share, was of days long since passed.

“It was slowly drifting, bobbing up and down,” she says. “The sails were all aflame and the fire seemed to be coming from the bottom of the boat.

“The colour was just indescribable. It was beautiful.”

The sails crashed down and its Waterloo was becoming ever clearer.

Eventually, the French couple re-entered the cab and left, and Godin, still in shock by what she saw continued to her destination on foot.

Godin took one last glance at the disaster on the sea and could only see its outline in a blueish glow. The sails back in their original place.

“It was really eerie. Really strange,” she admits.

THE POST MORTEM

All who listen to Godin’s tales, whether they be family or curious attendees of her heritage discussions, are rapt.

Many documentarians and TV shows, such as Shadowhunters, have traveled to the northeast part of the province to investigate the bay themselves.

It’s locked in by two peninsulas, Youghall and Carron Point, but it’s saturated in history with visitors from abroad always calling it a port.

THE FULL extent of Chaleur Bay covers quite the geographical imprint in New Brunswick.

There are a few islands and many channels within those natural gate posts and the harbour. The Mi’kmaq First Nations would summer there before the advent of European contact. It’s also where Jacques Cartier sought refuge for a brief time in 1534. French missionaries established Récollet Mission in 1619. Acadian refugees called the area home in 1755. Eventually, by 1797, British, Irish and Scottish settlers arrived.

They were all drawn to the four freshwater rivers that emptied into the bay as well as the riches in wild fruit and game.

Godin loves diving deep into this heritage, but she has yet to uncover just what kind of ship she saw. During the time of European contact, the British, French and Spanish were the superpowers, as it were, and she has attempted to tie the ship to one of those nations.

She has heard many stories from others brave enough to share them without being considered loony, but only one other has been close enough to see people and dogs aboard the inferno.

“Being that age (a teen), you forget about it,” she says. “’People ask, what do you think was happening on that boat? ‘Those people were being killed. They were being massacred’.

“To me, when I had time to think about it, we used to have a lot of pirates here, to me either pirates went aboard the boat, or there was a mutiny.”

Studying history has always been a part of Godin’s pursuits, but the ghost ship did not reappear in her consciousness until 30 years after.

Captain Craig was one of those pirates of infamy that skulked along the New Brunswick coast. He spoke a dialect of the First Nations language but also took advantage of the kind nature of Mi’kmaq.

However, Godin does not recollect any cannons or guns on the ship. The three-mast ship on the provincial flag doesn’t seem to factor in either, nor do the British boats used to deport the Acadians in 1755, at the behest of Governor Charles Lawrence.

“If I could describe the boat, they could determine if it was the 1700s and 1800s,” she admits.

As for digging up the past in the bay, Godin has mentioned that she would love to solve the mystery, but it’s not often she’s focused on it.

“I haven’t been working on it, but I know if I read of any ships, or of the phantom ships, I want to see what the (witnesses) saw. I’ll read anything that’s on it.”

Many objects have been uncovered from the harbour, but really Bathurst harbour was such a busy port that it’s hard to separate what’s from what era and what’s from the phantom ship.

When it comes to getting help from others, it’s fleeting, much like the vision she saw.

“People just want to talk about it,” she says. “They’re not interested in where it came from.”

VIDEOGRAPHER’S FANCY

Also trying to attempt answering the unanswerable about New Brunswick folklore is videographer Alex Vietinghoff.

The digital associate producer at CBC refrained from providing his own experience as he had just been hired, but he did offer his eight-minute short documentary on the experience his cousin Owen had.

He edited together B-roll and interviews with family members to help illustrate the mythos that is the Fireship of Baie Des Chaleurs, as it is known as en Français.

Ships, boats and any other watercraft intrepid enough to attempt rescue can never catch the mirage as it bobs further away from them, a veritable dollar on a string.

Of course, those who are skeptical at heart, provide the theories of optical illusions and marsh gas.

PUT ME UNDER

Many artists’ interpretations of the Chaleur Bay ghost ship have little impression on Godin. They’re not accurate in her view.

“What artists do is it never gives the ship justice,” she says. “They should talk to someone who saw it.”

Therein lies the rub, as Godin candidly admits she wants to be put under hypnosis so she can dredge up the details that have sunk to the bottom of her memory banks.

“Maybe I can recall things that have slipped my mind,” she admits. “I know I wasn’t imagining it.”

With any brush with the preternatural, the answer is often as murky as the watery graves countless ships have descended into.

Sometimes it’s better to leave the secrets in Davy Jones’ locker.